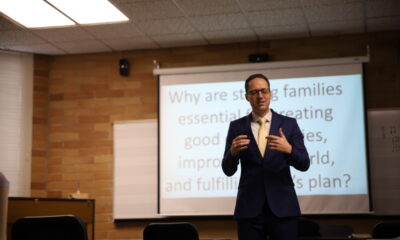

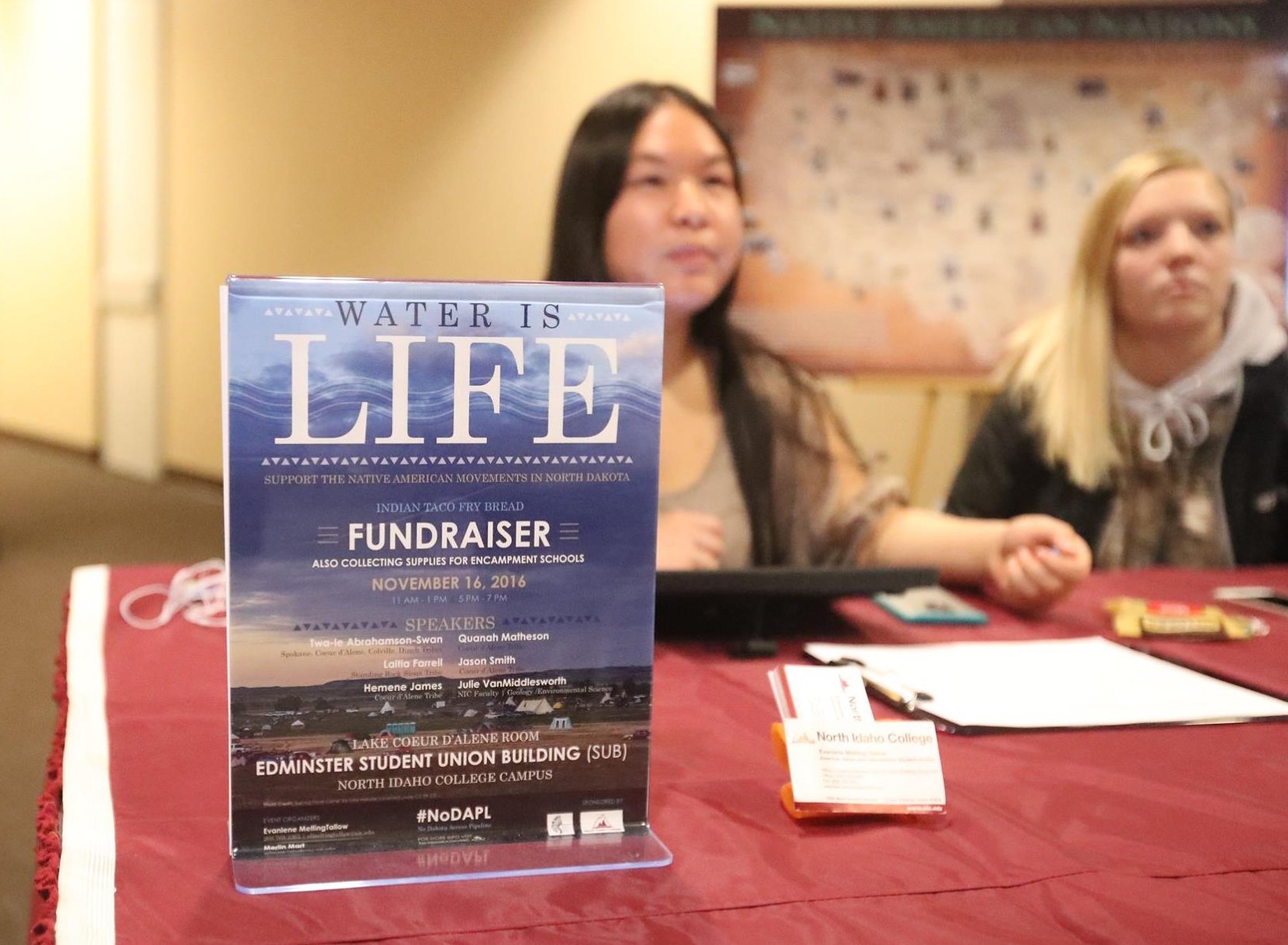

It was a small group of early birds at the coffee connection, up early at 7 a.m. to learn about how Federal Indian Policy affects the tribes in Idaho.

Inside the Human Rights Institute, Rhylee Marchand, the in-house attorney for the Coeur d’ Alene tribe, gave a presentation on Nov. 9 with a brief history of how the U.S. policy has evolved and affected Idaho’s native tribes. This event was held as one of the activities scheduled by the Coeur d’ Alene Tribe for Native American Heritage Month.

In Marchand’s presentation, she listed a number of stages of governmental involvement in Native American life. Starting with the Removal, Reservation and Treaty period and moving to the Self-Determination Period, she said Native Americans have been subject to a lot of governmental control and change.

In the Removal, Reservation and Treaty Period (1828-1887), natives were forced by U.S. military to migrate and relocate to large tracts of land, or reservations, designated specifically for them. Then, due to the Dawes Act, the Allotment and Assimilation Period (1887-1934) split up the reservation lands, giving specific allotments to natives, and selling the rest of the land to settlers.

“It’s really disheartening,” Marchand said. “It’s disheartening looking at how it went on for so long… But it’s kind of just a way of life that we have to deal with now.”

The Indian Reorganization Act/Period (1945-1968) restored the natives their land and helped tribes organize their own governments. But the Termination Period ended all governmental assistance to the native programs and encouraged natives to disperse and blend in with the rest of U.S. culture, causing a loss of cultural identity.

“We look at the way that Native American children are brought up and it’s a lot different than mainstream culture,” Marchand said. “But it’s kind of a way of life.”

By the Self-Determination Period (1968 – present,) the U.S. government realized the negative affects of the Termination Period and pushed for native’s self-governance and control over their own lands.

“It’s still happening, it’s not as traumatic as it was during those times, but definitely a necessity. It’s kind of a double-edged sword for sure,” she said.